Toots Zynsky a Palazzo Loredan

"My current technique, which I named Filet-de-Verre, has evolved from more than thirty years of utilizing all other known methods of glass forming (including glass blowing, Pate-de-Verre, fusing, slumping, casting, etc.).

Filet-de-Verre involves first pulling (by special machine) large quantities of glass thread from larger colored Italian glass cane from Murano.

This then becomes my raw material.

My pieces consist of many layers of threads laid out flat on a heat resistant ceramic fiber board.

Laying out each piece is a similar thought process to making a drawing or a painting.

When I feel that the piece is complete, it goes in the kiln for fusing.

As soon as it is thoroughly fused, I begin immediately transferring it to a series of preheated molds giving it a basic deep round form.

Constantly taking it in and out of the kiln to reheat it, I then begin free forming it by squeezing and pulling.

Sometimes briefly laying it upside down over a simple cylinder to allow it to drape down giving it more natural flowing curves following the folding I have already predetermined at the edges.

Then like any hot glass it needs to cool down slowly - for up to two days.

The pieces are basically finished in the kiln.

When they come out - hopefully intact - they are brushed and washed and touched up with diamond files and... Voila."

Toots Zynsky

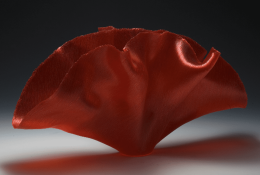

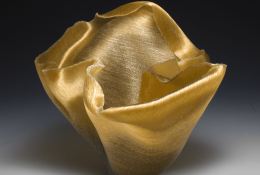

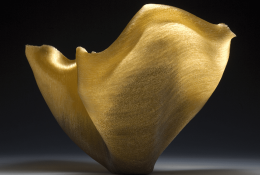

For a contemporary artist like Zynsky, the bowl form is interesting less for its metaphysical suggestiveness than for the intricate relationships between inside and outside surfaces. The inside/outside contrast is central to the way her bowls are conceived, executed, and experienced, so one supposes the bowls must remain empty, since any content would conceal much of their inner surfaces.

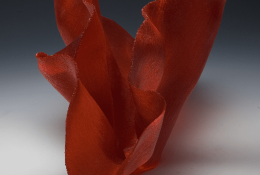

The openness of the bowl form, maximally exposing the concave inner surface, enables the dialogue between inside and outside to take place. One question is how high the sides can be in order to maintain the dialogue. If too high, the bowl is transformed into a vase; if too low, it becomes a plate, and in neither case can the inside and outside be brought together as one aesthetic experience. Zynsky is driven by a kind of daring to increase the wall's height, and correlatively to increase the bowl's depth. But then the opening must be proportionately wide to keep the inner surface in view.

The inside/outside relationship finally controls the proportions and the shapes of the vessels. The base of a bowl is typically smaller in diameter than the mouth, so the walls flare out like the sides of opening flowers.

Many craftspersons, bent on obliterating the distinction between craft and art, have shunned any reference to utilitarian objects, and prefer to describe themselves as sculptors in clay or glass or whatever. One can imagine Zynsky making abstract sculptures in glass, using the same techniques she now uses to make her bowls. But the interplay between the obverse and reverse surfaces works best when we have no doubt as to which is inner and which outer. So in a way, she depends upon our familiarity with bowls. This familiarity facilitates her aesthetic in a nearly unique way. So why should she look afield for a different form? Why not consider her work as bowlshaped sculptures in glass?

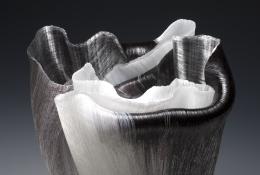

Since the walls are deeply but irregularly fluted, the works take on a baroque opulence of impulsive curvatures.

A main function of the fluting is to give glimpses of the inner surface as we look at the bowl's outside. The flutings, of course, are extremely expressive, and the shaped glass reveals the history of sculptural decisions which have gone into its final form.

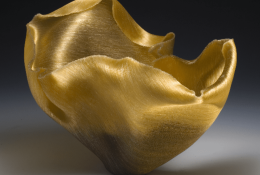

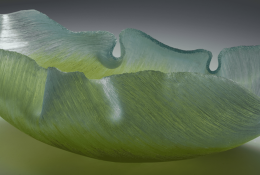

The bowls also reveal the technical history of Zynsky's ways of working with glass. They are made of fused glass rods thin enough to speak of as threads. These give a stiff texture to the surfaces, but they also mark differences between inside and out, since the two sets of threads often run in different directions, and have distinguishable colorations. The artist has more or less invented these techniques, as much a part of her style as her indented, flared forms and the iridescence of her hues. This is where the language of glass threads comes in.

There are in principle two layers of threads, corresponding to the bowl's inside and outside. The bottom layer will typically be composed of colored threads, arranged to form abstract patterns sometimes reminiscent of Morris Louis' paintings. This stage of the work is, in a sense, a form of painting. Zynsky uses a palette of about 60 colors, and her assistants spend much of their time making the threads, using a contraption a Dutch engineer improvised for her.

The top layer, by contrast, is made of clear glass threads. When these are fused under heat; they form a kind of translucent lining, muting the often vivid colors of the external surface. Sometimes the layers, and hence the inside/outside contrast, will be reversed, with the inside vivid and the outside muted. In any case, the anatomy of the bowl is complete when the two layers of threads are complete, and the process of shaping the disk sculpturally into a bowl can begin.

The threads retain their separateness after fusion, so the bowl gives the appearance of being made of fibers, slightly rough to the touch. The texture adds a dimension to the veils of intense color-and makes its own contribution to the aesthetics of concave and convex.

Toots Zynsky learned the art of glassblowing at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in the early I970s. Under the leadership of Dale Chihuly, glasswork has been revolutionized from one of the traditional crafts into a marvelously contemporary art. Drawing on the past but driven by the inventiveness of the I96os, members of the RISD glass studio must have had the sense of being at the beginning of something vast and uncharted.

American glasswork has kept the excitement of its beginnings ever since.

Her bowls do not, as it happens, make use of glassblowing. Zynsky claims that only someone deeply versed in that technique could handle glass the way her bowls demand. Zynsky in fact uses metal bowls as molds for forming her shapes: the softened disk is fitted into the metal bowl the way dough is fitted into a pie pan, and then allowed to harden. Removed, reheated, fluted, and folded, her bowls attain their astonishing final shape through the traditional procedures of manipulating glass.

In an age in which the relevance of beauty to art is widely questioned, Zynsky's work is uncompromisingly beautiful. It is, however, what the poet Andre Breton would have called convulsive beauty. The intensity of adjoined color, the tactile vitality of fluted walls, the swirling energies of shape and pattern are transformed into a luminous whole through the interaction between glass and light. That is the final reason for keeping the bowls empty. Content would obscure the interaction. Her bowls are among the most beautiful objects made, but their beauty is a product of the material and processes of artistically transformed glass.

Arthur Danto